CS 3110: Data Structures and Functional Programming

Week 1. Overview

What is a functional language?

A functional language

- defines computations as mathematical functions

- avoids mutable state

- specifies what to compute

- Variables never change value

- Functions never have side effects

- is a powerful way to build correct programs

Mutability

A major reason why we use functional languages is the fantasy of mutability. This is the idea that a machine performs operations on a state sequentially.

- The reality is that machines are good at complicated manipulation of a state while humans are not good at understanding it.

- Mutability breaks referential transparency: the ability to replace an expression with its value without affecting a computation. For example, both function $f(x) = x^2$ and $g(x) = x^2$ are the same function and can be swapped. However, to Java these are two different functions.

Imperative programming

Imperative programming is what we learned in Java. Commands specify how to compute by destructively changing a state. Some examples are

x = x+1;

//This doesnt make sense in math speak,

//so why do programmers use it??

a[i] = 42;

p.next = p.next.next;

In imperative programming, functions and methods not only return a value, but also have side effects.

Why study functional programming

- Functional languages teach you that programming trasncends programming in a language

- Functional languages predict the future

- Some features such as garbage collection, type inference and generics (Object

) were implemented in functional languages way before they were in Java.

- Some features such as garbage collection, type inference and generics (Object

- Functional languages are sometimes used in industry

- Functional languages are elegant

OCaml

Ocaml stands for Objective Categorical Abstract Machine Language (not a helpful acronym). There are object oriented features in OCaml, but we will not use them.

13. Learning a Programming Language

There are 5 aspects of a programming language that we will keep in mind when learning a new language.

- Syntax: How do you write language constructs?

- Semantics: What do programs mean?

- Semantics is a meta tool. It will help you learn languages

- Idioms: What are typical patterns for using language features to express your computation?

- Idioms will make you a better programmer in a language

- Libraries: What facilities does the language provide as “standard”?

- Tools: What do language implementations provide to make your job easier? (E.g., top-level, debugger, GUI editor, …)

Syntax is always boring! Focus on semantics and idioms.

14. Expressions

Expressions have two pieces: syntax and semantics.

Semantics involves type-checking rules (static semantics). These produce a type or fail with an error message. It is static because although the compiler is run, the program is not run yet.

Semantics also involves evaluation rules (dynamic semantics). These produce a value, or exception or infinite loop.

Definition (value). A value is an expression that does not need any further evaluation.

Example (int). In utop, let us type a couple statements.

# 3110;;

- : int = 3110

# false;;

- : bool = false

# 3110 > 2110;;

- : bool = true

# "big";;

- : string = "big"

# "big" ^ "red";;

- : string = "bigred"

# 9 + 10;;

- : int = 19

This means that 3110;; evaluates to the int 3110.

Proposition (Ocaml does not have overloading). Note that no operators in OCaml are overloaded. Floats need specific operators different from the int operators.

# 2.0 * 3.14;;

Line 1, characters 0-3:

Error: This expression has type float but an expression was expected of type

int

# 2.0 *. 3.14;;

- : float = 6.28

Type inference and annotation

Note that the OCaml compiler infers types. It checks types at compile time.

- The compiler will fail with a type error if it can’t infer a type.

- The hard part of language design is guaranteeing the compiler can infer types when a program is written correctly.

In OCaml, you can manually annotate types anywhere.

- Replace $\tt e$ with $\tt (e:t)$.

- This is useful for diagnosing type errors.

# (3110 : int);;

- : int = 3110

# (3110 : bool);;

(* This gives an error*)

15. Let Definitions

Let definitions are like variable definitions in other languages, except the values cannot change.

# let x = 42;;

val x : int = 42

# x;;

- : int = 42

Definitions

A definition is a way of giving a name to a value.

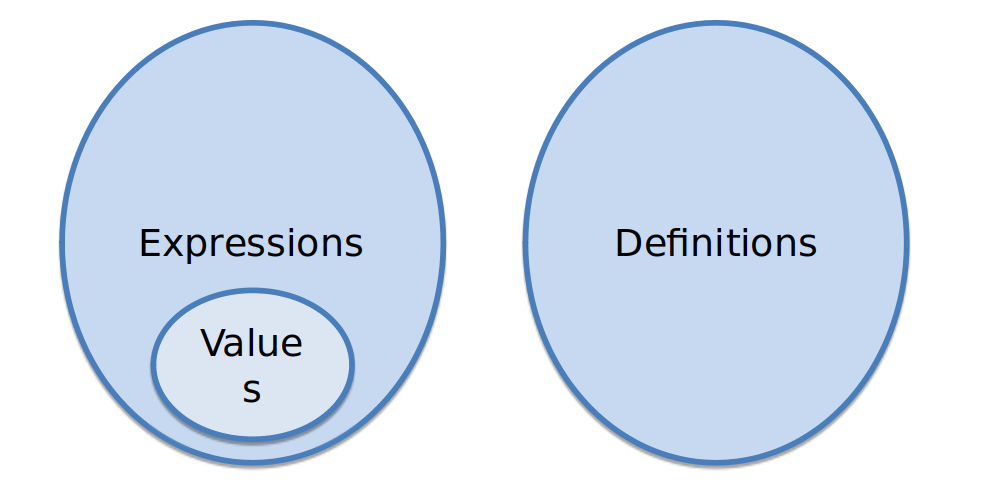

- Note that definitions are not expressions, or vice-versa! By definitions syntactically contain expressions.

$\tt let$

The syntax for the let statement is as follows:

\[\texttt{let x = e}\]where $\tt x$ is an identifier.

The evaluation of the let statement occurs in this order:

- Evaluate $\tt e$ to a value $\tt v$.

- Bind $\tt v$ to $\tt x$; henceforth, $\tt x$ will evaluate to $\tt v$.

- Under the hood, $\tt x$ is a pointer to the memory location that contains $\tt v$.

Note that $\tt x$ itself is not an expression!

(let x = 1) + 2;;

Error: Syntax error: operator expected.

16. If Expressions

If expressions follow the syntax

\[\texttt{if e1 then e2 else e3}.\]- If $\tt e1$ evaluates to $\tt true$, and if $\tt e2$ evaluates to $\tt v$, then $\texttt{if e1 then e2 else e3}.$ evaluates to $\tt v$.

- If $\tt e1$ evaluates to $\tt false$, and if $\tt e3$ evaluates to $\tt v$, then $\texttt{if e1 then e2 else e3}.$ evaluates to $\tt v$

Type checking:

- If $\tt e1$ has type $\tt bool$ and $\tt e2$ has type $\tt t$, and $\tt e3$ has type $\tt t$, then $\texttt{if e1 then e2 else e3}.$ has type $\tt t$.

For example,

if "batman" > "superman" then "yay" else "boo";;

This is very similar to the ternary operator.

Note that OCaml will be strict about types. The if statement must have type bool. The two branches of the if statement must be of the same type.

The else branch is also required.

17. Let Expressions

Let expressions are like let definitions, but they can be nested together. They have the form

\[\texttt{let x = e1 in e2}.\]Evaluation rule (dynamic semantics):

- Evaluate $\tt e1$ to a value $\tt v1$.

- Substitute $\tt v1$ for $\tt x$ in $\tt e2$, yielding a new expression $\tt e2’$.

- Evaluate $\tt e2’$ to a value $\tt v2$.

- The result of $\texttt{let x = e1 in e2}$ is the value $\tt v2$.

Type checking rule (static semantics):

- If $\tt e1:t1$ and consequently $\tt x: t1$, and $\tt e2:t2$, then $\texttt{(let x = e1 in e2): t2}$.

Note that this does not bind a value to any variable! This is because of the variable’s scope “in” an expression.

# let a = 0 in a;;

- : int 0

# let b = 1 in 2 * b;;

- : int 2

# a;;

Error: Unbound value a

# let c = 5 in (let d = 3 in c + d)

- : int 8

In addition, the following statement is tricky to understand, but valid:

let e = 5 in (let e = 6 in e);;

Line 1, characters 4-5:

Warning 26: unused variable e.

- : int = 6

This code compiles because of the let expression’s type-checking rules and evaluation rules.

18. Variable Expressions and Scope

$\tt let$ in toplevel

In utop, any let definition is implicitly $\tt in$ the rest that you type.

Scope

The scope of a variable is where its name is meaningful.

let x = 42 in

(* y is not meaningful here *)

x + (let y = "3110" in

(* y is meaningful here *)

int_of_string y)

Name

Principle of Name Irrelevance: the name of a variable shouldn’t intrinsically matter.

For example, in math, the following are the same functions:

- f(x) = x+1

- f(y) = y+1.

To ensure name irrelevance in programs, stop substituting when you reach a binding of the same name.

let x = 5 in x + (let x = 6 in x + x))

- : int = 17

19. Scope and the Toplevel

In utop, the following is legal, giving the illusion of mutability.

let x = 1;;

let x = 2;;

x;;

In reality, it is just nested scopes.

let x = 1 in

let x = 2 in

x

2.3. Functions

Recall from week one that the following code

let x = 42

has an expression in it, but is not an expression itself. Rather, it is a definition since it binds values to names. In OCaml, functions must begin with lowercase letters.

A function definition is a particular type of definition defined like this:

let f x = ...

Recursive functions are defined with the rec keyword:

let rec f x = ...

Example (factorial).

(* Precondition: Requires n >= 0*)

(* Returns: n!*)

let rec fact n =

if n = 0 then 1 else n * fact(n-1)

(* Requires y >b 0*)

(* Returns x^y*)

let rec pow x y =

if y = 0 then 1

else x * pow x (y-1)

(* Power with type annotations*)

let rec pow (x:int) (y:int) : int =

if y = 0 then 1

else x * pow x (y-1)

Mutual recursion can also be implemented with the and keyword.

(* [even n] is whether [n] is even.

* requires: [n >= 0] *)

let rec even n =

n = 0 || odd (n-1)

(* [odd n] is whether [n] is odd.

* requires: [n >= 0]*)

and odd n =

n <> 0 || even (n-1)

Dynamic semantics of functions

- Functions do not have dynamic semantics since nothing is evaluated. Function $\tt f$ has arguments $\tt x1…xn$ and body $\tt e$.

Static semantics of functions.

- For non-recursive functions, assuming that $\tt (x1:t1) \dots (xn:tn)$ and $\tt e: u$, $\tt f$ is the map

- For recursive functions, assuming that $\tt (x1:t1) \dots (xn:tn)$ and $\tt e: u$ and $\tt f : t1\to t2\to\dots\to tn\to u,$ we can conclude that $\tt f : t1\to t2\to\dots\to tn\to u.$

- Note that the recursive static semantics assumes that $\tt f$ has a particular type.

2.3.1 Anonymous Functions

An anonymous function is one that does not have a name. They are denoted with the fun keyword. Here are two increment functions. One is anonymous and one is not.

let inc x = x + 1

let inc = fun x -> x+1

Anonymous functions are also called lambda expressions, a term from lambda calculus. This was a model of computation in the same sense that Turing machines are a model of computation.

Since functions are values, they can be used anywhere we use values. Functions can take arguments as functions and return functions as results.

Dynamic semantics.

- Since anonymous functions are already a value, no computation is performed.

Static semantics.

- If by assuming $\tt (x1:t1) \dots (xn:tn)$ we can conclude that $\tt e :u$, then $\tt fun \space x1 \dots xn \to e : t1 \to \dots \to tn\to u$.

2.3.2. Function Application

Function application is written by just putting functions next to each other.

Given the syntax

e0 e1 e2 ... en

the first expression $\tt e0$ is the function, and $\tt e1 \dots en$ are arguments.

Static semantics.

- If $\tt e0: t1 \to \dots \to tn \to u$ and $\tt (e1:t1) \dots (en:tn)$, then $\tt e0 \space e1 \dots en : u$.

Dynamic semantics.

- Evaluate $\tt e0$ to a function. Also evaluate the arguments $\tt e1 \dots en$ to $\tt v1 \dots vn$.

- For $\tt e0$, the result might be an anonymous function $\tt fun \space x1 \dots x-n \to e$ or a name $\tt f$.

- Substitute each value $\tt vi$ for the corresponding argument name $\tt xi$ in the body $\tt e$ of the function. The substitution results in a new expression $\tt e’$.

- Evaluate $\tt e’$ to a value $\tt v$, which is the result of evaluating $\tt e0 \dots en$.

Anywhere $\tt let \space x = e1 \space in \space e2$ occurs, we could replace it with $\tt (fun \space x \to e2)e1$.

Pipeline

| There is an infix operator in OCaml called the pipeline operator $\tt | >$, which is equivalent to the function application. Values are sent through the pipe from left to right. For example, with functions inc and square, here are two equivalent functions. |

let (|>) x f = f x

square (inc 5)

5 |> inc |> square

(*both yield 36 *)

This improves the readability of code since less parenthesis are used. Here is another example:

5 |> inc |> square |> inc |> inc |> square

The forward application operator is

let (@@) f x = f x

succ (2 * 10)

succ @@ 2 * 10

2.3.3. Polymorphic Functions

The identity function is the function that simply returns its input.

let id x = x;;

id : 'a -> 'a = <fun>

Here, $\tt ‘a$ is a type variable, which stands for an unknown type. Type variables begin with a single quote.

Because $\tt id$ can be applied to multiple types of values, it is a polymorphic function.

2.3.4. Labeled and Optional Arguments

It can be useful to label functions with many arguments. For example, String.sub is labeled, indicating that it probably operates on strings.

String.sub;;

-: string -> int -> int -> string

In OCaml, you can label arguments with the following syntax:

let f ~name1:arg1 ~name2:arg2 = arg1 + arg2;;

val f : name1:int -> name2:int -> int = <fun>

The function can then be called by passing arguments in either order.

f ~name2:3 ~name1:4

7

To make the variable name same as the label, OCaml supports the following syntax, which are equivalent

let f ~name1:name1 ~name2:name2 = name1+name2

let f ~name1 ~name2 = name1 + name2

Explicit type annotations can also be added.

let f ~name1:(arg1:int) ~name2:(arg2:int) = arg1 + arg2

Optional arguments can also be added with a default value.

let f ?name:(arg1=8) arg2 = arg1 + arg2

f ~name:2 7

f 7

2.3.5. Partial Application

Partial application is when a function is partially applied to one argument when it can take multiple.

Example. Suppose we have the following add function:

let addx x = fun y -> x + y

addx takes an int and returns a function of type int -> int. Something interesting we can do with addx is the folowing:

let add5 = addx 5

add5 2

In fact, this is how add is implemented in OCaml. The statement let add5 = add 5;; is completely legal.

To recap, here are several semantically equivalent ways of writing add

let x y = x+y

let add x = fun y -> x + y

let add = fun x -> fun y -> x + y

Recall that functions are values, so

- functions can take functions as arguments.

- functions can return functions as resuts.

Function associativity

The reality of OCaml is that every function takes exactly one argument.

A function $\tt f$ takes in an argument and evaluates types in a right associative manner. To illustrate,

t1 -> t2 -> t3 -> t4

is equivalent to

t1 -> (t2 -> (t3 -> t4))

Notice that this differs from function application, which is left associative.

2.3.6. Operators as Functions

Operators can be written in prefix notation by putting parenthesis before them ( + ). We can even define our own infix operators.

let ( ^^ ) x y = max x y

2 ^ ^ 3

-: 3

3.1.1. Lists

In OCaml, a list is a sequence of values with the same type. They are singly linked and immutable.

- They are good for sequential access of shot to medium length lists (say up to 10k elements).

Building Lists

Syntax. In OCaml, there are 3 ways to build a list:

[]

e1::e2

[e1; e2; ...; en]

The first is an empty list. The second prepends e1 to e2. The operator is called “cons”’, short for constructs. $[]$ is pronounced “nil”, from Lisp.

The third is just syntactic sugar for ::.

[1; 2; 3] = 1::2::3::[]

Evaluation.

- $\tt []$ is a value.

- To evaluate $\tt e1 :: e2$,

- Evaluate $\tt e1$ to a value $\tt v1$.

- Evaluate $\tt e2$ to a value $\tt v2$

- Evaluate $\tt e2$ to a list value $\tt v2$ and return

- $\tt v1 :: v2$.

This is the same for the bracket notation $\tt [e1; e2]$.

List Types

For any type $\tt t$, the type $\tt t\space list$ describes lists where all elements have type $\tt t$.

[1; 2; 3] : int list

[true] : bool list

[[1 + 1; 2 - 3]; [3 * 7]] : int list list

List Semantics

For nil, an empty list, the type is $\tt [] : ‘a \space list$.

For cons, if $\tt e1: t$ and $\tt e2: t \space list$, then $\tt e1 :: e2 : t \space list$.

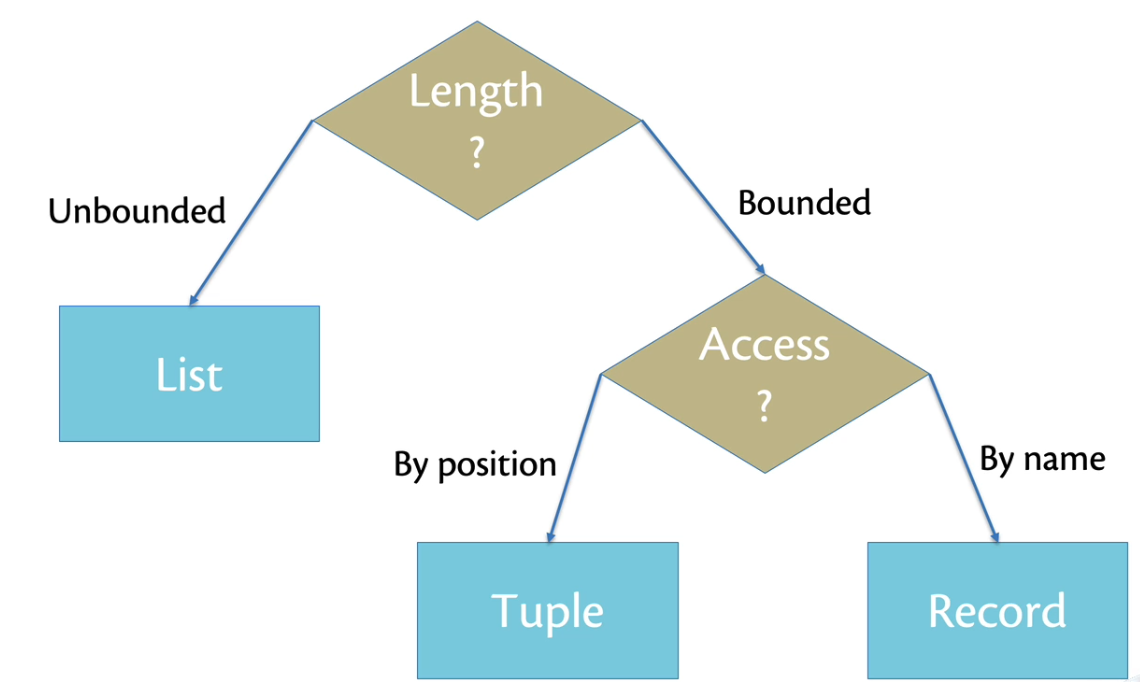

Records and Tuples

Records

A record is similar to a struct in C.

type student = {

name : string;

year : int; (* grad year *)

}

let rbg : student = {

name = "Ruth Bader";

year = 1954;

}

Syntax. To understand records, we will introduce a new kind of definition, a type definition.

$\tt {f1 = e2; f2 = e2}$ is a record with fields named $\tt f1$ and $\tt f2$. The order of fields is irrelevant. The dot operator accesses a field from expression $\tt e$.

- Field names are identifiers not expressions.

Dynamic Semantics. If $\tt ei \to vi$ then $\tt {f1 = e1; \dots; fn = en} \to {f1 = v1; \dots; fn = vn}$.

If $\tt e \to {…; f = v; …}$ then $\tt e.f \to v$.

Static Semantics. Record types must be defined before used so OCaml knows the field names.

Record Copy

$\texttt{e with f1 = e2; f2 = e2; \dots }$ creates a copy of $\tt e$ with a new field value for $\tt f1$. Remember that you cannot add new fields.

Tuples

A tuple is an unnamed record.

type time = int * int * string

let t : time = (10, 10, "am")

type point = float * float

let p = (5., 3.5)

There is a function $\tt fst$ that takes in a tuple pair and returns the first value.

Syntax. The order of tuples are important. $\tt (e1, e2, e3)$.

Dynamic Semantics. If $\tt ei \to vi$ then $(e1, \dots, en) \to (v1, \dots, vn)$.

Type Checking. If $\tt ei : ti$ then $\tt (e1, \dots, en) : t1 * \dots * tn$.

Comparison

When deciding what data type to use, here are some considerations.

Pattern Matching

A list can be

- nil

- the cons of an element onto another list

Pattern matching on a list works only in these 2 ways.

let empty lst =

match lst with

| [] -> true

| h :: t -> false

Syntax. The syntax takes the general form

match e with

| p1 -> e1

| p2 -> e2

$\tt p$ is a new syntactic class: pattern expressions.

Static Semantics. If $\tt e$ and $\tt pi$ have type $\tt ta$ and $\tt ei$ has type $\tt tb$, then the expression as type $\tt tb$.

Dynamic Semantics. Evaluate $e$ to a value $v$. Then proceed top to bottom. If e matches with $\tt pi$, then $\tt ei \to vi$. Then, the expression evaluates to $\tt vi$.

If no patterns match, raise an exception $\tt Match_failure$.

In pattern matching,

- a constant matches itself

- an identifier, pattern variable matches to anything and binds it to the scope of the branch

- The wildcard matches to anything but does not bind to it.

Function keyword

Immediately matching against an implicit final argument is so useful that there is syntactic sugar for it.

let f x y z =

match z with

| p1 -> e1

| p2 -> e2

let f x y = function

| p1 -> e1

| p2 -> e2

Append

Append combines two lists. Keep in mind it is linear time with the first list, like what we saw in our implementation.

let rec append lst1 lst2 =

match lst1 with

| [] -> lst2

| h :: t -> h :: (append t lst2)

[432] @ [432]

'a list -> 'a list -> 'a list